ARTICLE

Access to unlicensed medicines, who should pay when they are not provided for free?

Originally published 6 September 2021 at: https://doi.org/10.1177%2F23992026211040047

Abstract

The rising cost of clinical development, license submissions, commercial product launches, and affiliate management in all countries around the world, coupled with the ethical obligation to ensure that eligible patients have access to new treatments, has led some pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical companies to review their approach to access to medicine.

The traditional US first launch, followed by European Union approval and then a strategic launch process, can eventually ensure access in the key markets with developed healthcare systems. For many other countries, providing access via the current legislation available for unlicensed medicine supply can provide a solution for increasing access.

This option can be considered for broadening access to a greater number of eligible patients in more countries where unlicensed supply may be the only option, for example, if no clinical trials or commercial product supplies are available. This article looks specifically at the key financial and reimbursement considerations for unlicensed medicines and how some companies are adopting a “charged for” early access model that can be sustainable and affordable from their perspective.

It is also important to consider how sustainable a charged program would be for the patient and the relevant payer, as they may expect an unlicensed treatment is provided free of charge. However, if the sponsor or manufacturer simply cannot afford to run a free supply program, the patient is faced with a more serious problem, that of no access at all, either charged or free.

The objective of this article is to raise awareness amongst interested stakeholders from different perspectives, including the patients. Unlicensed medicines are usually only prescribed when there is a serious or life-threatening unmet need, and the implications for the company, physician, patient, and payer should be clear if access to treatment depends on the ability to pay.

Introduction

Early Access, International Pharmacy, Named Patient Supply, or Pre-Approval Access Programs are all commonly used terms for what is essentially the same thing, the ethical and legitimate supply of medicine into a country where it does not have a license. It could be that the treatment is still in late phase development, although this is uncommon for a charged access program, as the risk versus benefit is more delicate before approval in at least one major country.

Charging is more common once the treatment has a license in at least one country and a commercial pack is available, but the medicine is not yet licensed in the country where it is needed by the physician to treat an unmet medical need. Unlicensed supply programs can be implemented on a patient-by-patient basis or, in some countries, for a group of patients.1

The regulatory mechanisms that exist vary from one country to the next and in most places where there is a reasonably well-established healthcare system a defined approval process will exist that can be followed by the treating physician who wants access to an unlicensed medicine. (These requests are not always approved by the local competent authority).

Providing supply is available and there is limited or no licensed alternative, the treating physician should be able to make a compelling case for approval. It is also important to point out that the primary purpose of such programs is access and not to collect data, generate revenue, or for any other purpose outside of ensuring patients who otherwise could not access treatment can do via such a program.2

Some secondary benefits might be appropriate for some treatments, such as data collection,3 but this must be kept within the context of the primary purpose which is access to treatment. These programs can also help to bridge the “access gap” that exists at any time during a drug’s lifecycle when there is demand but the drug is not yet accessible either via an ongoing clinical trial or the usual prescription route for a licensed product.

Where a high unmet medical need exists, for example, in rare diseases4 and some forms of cancer, the treating physician may well have limited or even no licensed treatment options at all. Therefore, there is an urgent need for the manufacturer to consider how they will ensure equitable and fair access to as many eligible patients as possible, which is why a proactive approach to access is needed.

When a company establishes unlicensed access or named patient supply, it is usually for one of the following objectives:

- To make a treatment in clinical development available to patients who are unable to participate in a clinical trial.4

- To make treatment available to study participants after the completion of a study, but before it becomes commercially available (Post-Trial Access Program).5

- To make a treatment that has been approved in one country available in another country where it has not yet been approved or where approval is not expected.6

- To make treatment available when commercialization is unlikely to be pursued due to the very low number of eligible patients in a particular country, ultra-rare disease for example.6

- To make a drug available after development or commercialization in a specific market has been terminated but current patients still need treatment.6

In some cases, the manufacturer may choose to charge for supplying the treatment on an unlicensed basis, providing the local regulations permit chargeable unlicensed supply. Most countries will allow the manufacturer to set the price freely, as unlicensed supply routes are not normally linked to formal pricing and reimbursement process.

However, in some countries, such as France and more recently Italy, the price charged for a treatment supplied on an unlicensed basis is linked to the commercial price. This is a trend from competent authorities that the author sees increasing, as more companies are using the unlicensed supply route to improve access to their treatments globally, as is their ethical obligation. In the United States, where it is permissible to charge for an unlicensed medicine, very few companies choose to do so because of the complexity of the process and potential negative impact on the commercial selling price following Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval.

Also, in the United States, the time between pre-approval access and FDA approval is usually less than 12 months, so a relatively short period of free supply before commercial availability can be tolerated, unlike in Europe, where the wait for commercial availability can be much longer in some countries.

Current picture

A snapshot of 114 Early or Managed Access Programs managed by Clinigen shows that 50% are for an unlicensed treatment that was made available to physicians on a charged basis. In most cases, these 57 charged programs supplied a commercial pack that was licensed in another country but not yet licensed in the country it was supplied into; hence, the unlicensed supply route was the only option available for patients.

While prices vary considerably depending on the disease area and treatment type, it is fair to say a premium of around 20%–35% above the expected commercial price was applied, reflecting the costs associated with this type of specialist, patient-centric, supply mechanism. It should be noted that for a pharma or biotech company, using an individual named patient supply route for exceptions is more cost-effective than a full commercial launch in a country where demand is expected to be low.

Clinigen has delivered over 300 different access programs globally which highlights the prevalence of unlicensed access programs. Some of the most used oncology treatments have been supplied on an unlicensed basis before approval, to ensure that patients with an unmet need had access without having to wait for the sometimes long approval process in their own country.

The challenge for companies

The decision on charging or providing for free has huge implications for the patients with an unmet need, the physicians who want to use the drug, and the company which may have limited resources. Some smaller biotechnology companies may need to offset development costs and the cost of supplying treatment by charging or at least offering a hybrid approach where the drug is provided free for a period of time and then switched over to charged supply.

This will depend on the manufacturer’s launch strategy and local country plans on when to commercialize. Larger pharmaceutical companies may have more resources and can afford to provide free products while country-level approvals and launches are achieved. However, even the large companies are unlikely to have the bandwidth to launch in every country where there is an unmet medical need, and for this reason, they may also need to weigh up the long-term cost implication of free supply.

Once a decision has been taken on a charging strategy, setting an appropriate price for access to treatment on an unlicensed basis is the next hurdle, as any impact on the future commercial price will have significant commercial implications.7,8 In most cases, the unlicensed price will be set higher than the expected commercial price, as the additional complexity and risks involved in supplying unlicensed medicine are factored into the decision.9

In addition, not all countries will allow charging, so if a drug is made available for free in some countries because the local health authority regulations have made this mandatory, and charged in some countries, it can be a challenging situation from a reputational standpoint to manage. Communication to key stakeholders and patient groups is critical to ensure expectations are managed clearly from the outset. Finally, once charging strategy, price, regulations, and communication plans are set, the next big question is who will pay, which is the subject matter at the heart of this article.

The challenge for patients

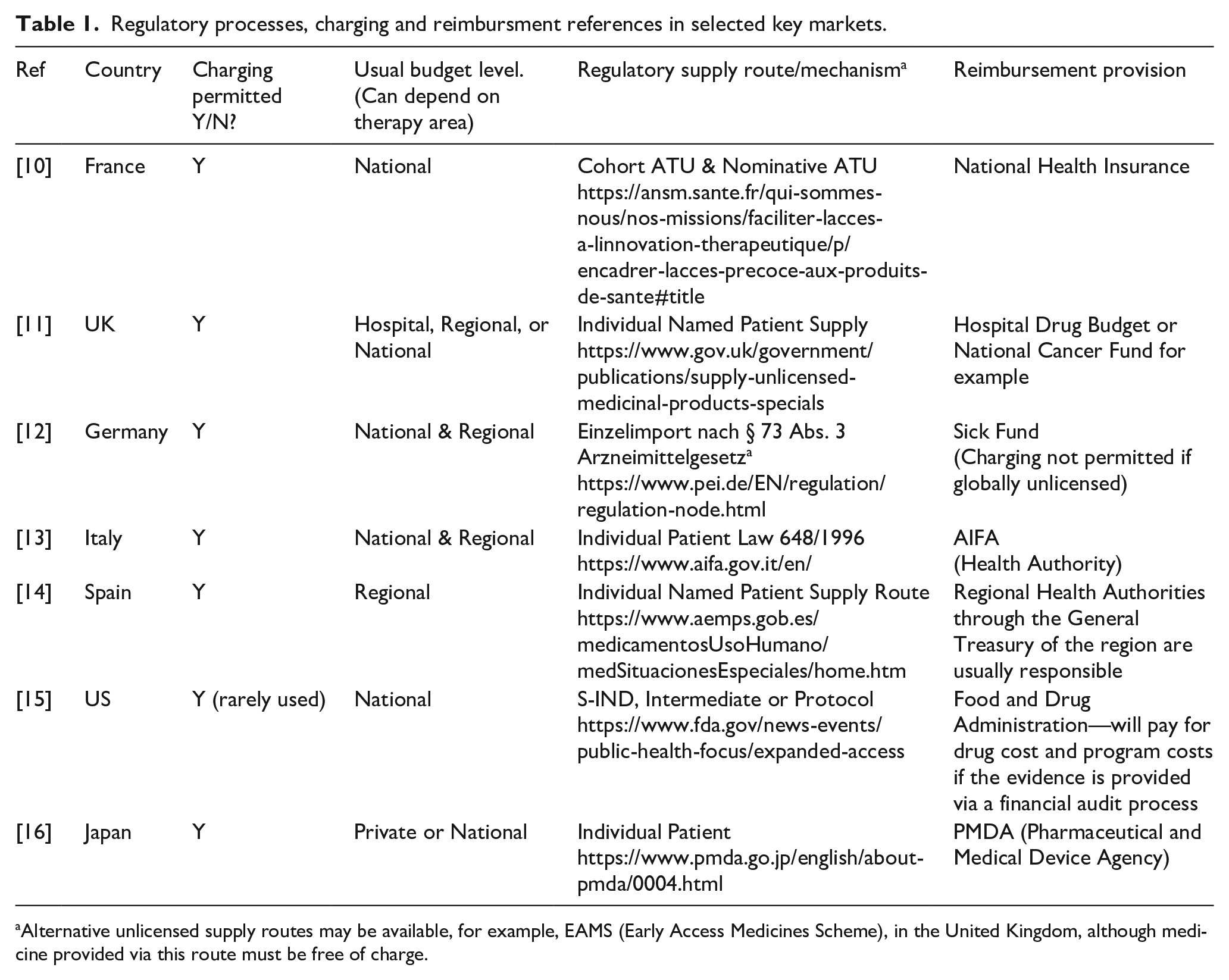

While some patients in some countries may have private insurance that covers the cost of medicine, even if unlicensed, many will not have and rely on public funding. The more developed countries with well-established and well-funded healthcare systems such as in the EU5 do have some procedures the physician can follow to secure funding for unlicensed treatments which are not listed on a compendium or formulary of approved drugs (Table 1).

In such cases, the motivation of the physician and often the pharmacist supporting the request is critical, as the procedure may involve additional paperwork, negotiation with finance, and meetings with colleagues to justify their decision to prescribe an unlicensed treatment. In oncology and rare disease, for example, patients are very well informed and can also be supported by well-organized patient organizations.

In these circumstances, the patient will often generate awareness and support for funding via social media and online forums, which creates attention that the manufacturer may not welcome, especially if public funding for the treatment is not available and therefore access is denied. To this end, let us look through the reimbursement pathways available in some countries for unlicensed medicine (see Table 1).

Table 1

The methodology for compiling the information in Table 1 comprised a review of relevant health authority websites to establish the procedure for unlicensed medicines supply and this was combined with the author’s own experience of payment mechanism used in each country. Clinigen maintains records of transactions where charged unlicensed medicine has been supplied and the budget source can be identified in most cases to establish a consensus for each country.

Options

For many countries, no formal process exists at the time of writing for reimbursement of a charged unlicensed medicine. While it is possible from a regulatory perspective to charge for an unlicensed medicine in nearly all countries in Europe, only the main EU5 markets have guidance on a reimbursement process that the author established during research for this article. Outside of Europe, reimbursement in the Middle East and LATAM regions, for example, appears to predominantly come from private insurance, with a few exceptions. Interestingly in China, where new unlicensed supply procedures are being tested in the Hainan region, private patient insurance is the only specified reimbursement option (Ref. Hainan Boao Lecheng International Medical Tourism Pilot Zone).

In the United Kingdom, Part VIIIB of the Drug Tariff (the “Specials Tariff”)17 is a tariff that includes some high-cost unlicensed medicines and imports, with set reimbursement prices. The prices are set by analysis of a selection of unlicensed manufacturer’s prices, with a margin included for pharmacy purchase profit. This medicines list will also encompass various formulations and preparations of licensed alternatives.

Spain14 provides another example of the variation in reimbursement processes for unlicensed medicines. Spain is divided into 17 autonomous regions that have broad powers concerning healthcare matters and are responsible for, among other things, supervising the dispensing and distribution of medicinal products. Funding requests for exceptional use of an unlicensed medicine will likely be processed through the relevant regional authority, in which case variation in decision-making can be expected. Decisions will also be impacted by therapy area, volumes, price, and the influence of the prescribing physician. Other countries in the European Union (EU) such as Italy and the United Kingdom may also adopt a regional or even hospital approach to a budget decision, again depending on the therapy area.

In the United States, the FDA has published “Charging for Investigational Drugs Under an IND” Questions and Answers, Guidance for Industry.18 This is an 11-page PDF that outlines requirements for charging and reclaiming drug costs.

There are three main perspectives to the reimbursement of an unlicensed medicine: (1) is charging permissible from a regulatory standpoint? (2) what is the price for the treatment? and (3) perhaps most importantly, who will pay? In order to ensure the most appropriate way forward, multiple stakeholders including healthcare professionals, payers, patient organisations and regulatory authorities should be consulted by the manufacturer. Conducting good quality market research on an individual country and therapy area level, is a good investment in time and should ideally include an assessment of the current local treatment guidelines, previously charged unlicensed treatments, existing reimbursement processes, the potential impact charging could have on the future commercial price, and patient forecasting.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the motivation of the prescribing physician is the key determining factor. If the unmet medical need can only be solved with an available unlicensed medicine, which is decided by the treating physician, and that medicine is only available on a charged basis, the treating physician with the support of colleagues is highly likely to negotiate to fund. It takes a very stubborn budget holder, for example, to object to funding in such circumstances and the debate can often escalate quickly into the public domain which will further complicate the issue and attract scrutiny for all players involved.

The decision to charge or to provide for free of charge will only become relevant after the decision to make medicine accessible to appropriate patients on an unlicensed basis has been taken. There are many important strategic aspects that a company should account for when planning charged unlicensed supply in addition to the need to provide access that would otherwise not be possible. In addition to the patient’s needs, the budget holder, the cost of running the program, potential revenue, the reaction from key customers to a charged program, and how sustainable the supply route will be for all the different stakeholders involved, and the potential impact on the commercial price.

We should all be willing to accept different perspectives and, where appropriate, lobby the relevant stakeholders to make reimbursement processes for unlicensed medicines more transparent.

References:

- Dickson, M, Gagnon, J-P. Key factors in the rising cost of new drug discovery and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2004; 3: 417–429.

- Pati, S. Early access programs: benefits, challenges, and key considerations for successful implementation. Perspect Clin Res 2016; 7(1): 4–8.

- Real World Data Collection via Early Access value , https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31228615/

- Early access to medicines in Europe: compassionate use to become a reality , https://www.eurordis.org/publication/early-access-medicines-europe-compassionate-use-become-reality

- Declaration of Helsinki . https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ (accessed 2 May 2018).

- Article 5 of Directive 2001/83/EC & Article 83 of Directive 2004/726/EC & 74 FR 40942 13th August 2009 in the USA .

- FDA Guidance on charging for unlicensed medicines , https://www.fda.gov/media/85682/download

- https://www.wepclinical.com/charging-investigational-drug/

- https://www.hma.eu/fileadmin/dateien/HMA_joint/02-_HMA_Strategy_Annual_Reports/08_HMA_Publications/2016_04_HMA_Compassionate_use_program.pdf

- Article L.5121-12 and Articles R.5121-68 to R. 5121-76 of the Public Health Code and Decree 2013-66 . **current processes, set to be updated 2021 to Compassionate Use (Nominative ATU) and Early Access Program (Cohort ATU) further details not available at time of writing

- Article 5 of Directive 2001/83/EC, Regulation 167 of The Human Medicines Regulations SI 2012 No 1916 .

- Ref. 73.5 of the Medicinal Product Act (Drug Law) .

- Ministerial Decree: Law n. 648 of 1996: if the product has no therapeutic alternatives, it may be added to the “648/96 LIST” and so every patient that needs it may have it . Law n. 326 of 2003: only if the product represents faith for severe illness, with a specific request and evaluation for every single patient, can be used the “5% fund” provided by ITA Regulatory Agency (AIFA).

- Royal Decree 1015/2009: availability of medicinal products in special situations .

- 21 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 312, Subpart I .

- MHLW Ordinance No. 9/2016: amending MHLW Ordinance No. 87/2014 on Good Clinical Practice for Drugs .

- https://psnc.org.uk/dispensing-supply/dispensing-a-prescription/unlicensed-specials-and-imports/

- https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/charging-investigational-drugs-under-ind-questions-and-answers